In the last lesson, we reviewed Phil Knight’s method for overcoming the many problems he faced. He called it his nightly catechism. As I read Knight’s words in Shoe Dog, I was reminded of a similar process that saved a number of lives. It was used by Hal Moore in a desperate battle in the Ia Drang Valley in 1965. I decided to read a bit more about it, so last week I read Hal Moore: A Soldier Once…and Always by Mike Guardia.

Lieutenant Colonel Moore was the commander of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry. It was early in the Vietnam war and North Vietnamese regulars had not really taken a leading role in the fight. In November of 1965, Moore and his men were flown into a clearing in the Ia Drang Valley. He would soon learn that they had landed adjacent to the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) base camp.

The American soldiers under Moore’s command were outnumbered nearly 4.5 to 1 (US Army, 450 to NVA 2,000), and at the end of a brutal, three-day battle, Moore had saved more than half of his men. He lost 79 killed and 121 wounded. The NVA lost 634 killed, and 1215 (estimated) wounded. That is a 1:9 ratio.[i]

The story of the battle in the Ia Drang Valley was recounted in the book We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, and it was later made into the movie, We Were Soldiers, starring Mel Gibson.

Lessons Learned

How did he do it? He had well-trained men and superior firepower, but he also engaged in particular leadership practices that made the difference in the midst of the battle. The movie did not depict this well, but during the battle, Moore would periodically withdraw to think and refocus himself.

Moore was debriefed after the battle so that the command could learn about how the NVA fought. According to General Sullivan in Hope is Not A Method, “When asked about his periods of seeming withdraw, Moore said that he had been reflecting, asking himself three questions: ‘What is happening? What is not happening? How can I influence the action?’”[ii]

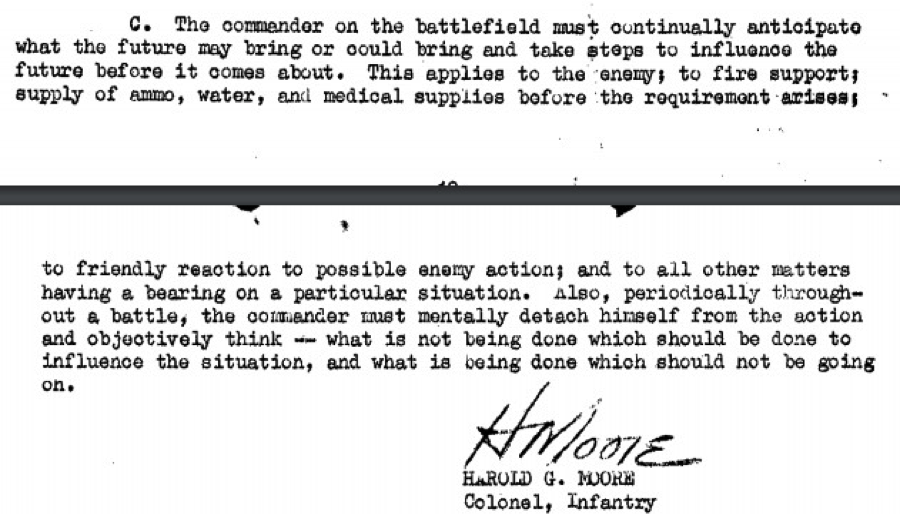

Moore’s official After Action Report contained great insight into the way Moore thought about his role. He wrote:

The commander on the battlefield must continually anticipate what the future may bring or could bring and take steps to influence the future before it comes about….Also, periodically throughout a battle, the commander must mentally detach himself from the action and objectively think—what is not being done which should be done to influence the situation, and what is being done which should not be going on.[iii]

What about you?

Think about the problems you are currently facing. Ask yourself:

- What is happening?

- What is not happening?

- How can I influence action?

References

[i] LZ Xray (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.lzxray.com/articles/lz-xray

[ii] Sullivan, G. R., & Harper, M. V. (1997). Hope is not a method: What business leaders can learn from America’s army. New York: Broadway Books. (pp. 46-47).

[iii] Hal Moore’s official After Action Report can be found at http://www.lzxray.com/articles/after-action-report

___________

Dr. Darin Gerdes is a tenured Professor of Management in the College of Business at Charleston Southern University.

All ideas expressed on www.daringerdes.com are his own.

This post was originally created for Great Business Networking (GBN), a networking organization for business professionals where Dr. Gerdes is the Director of Education.

___________